Hemorrhagic Necrotizing Retinitis

As the term suggests, hemorrhagic necrotizing retinitis (HNR) describes a group of disorders that causes severe inflammation of the retina leading to bleeding and retinal necrosis. There are only a few possible causes, which include infectious and inflammatory disorders. Classically, they are herpes simplex or zoster, syphilis, Behçet’s disease, and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Toxoplasmosis and fungal infection can also cause HNR. These all will be reviewed in this blog.

Acute Retinal Necrosis

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) is the classic form of hemorrhagic necrotizing retinitis. It is traditionally caused by herpes viruses, most commonly herpes simplex virus (HSV) or varicella zoster virus (VZV), and sometimes cytomegalovirus (CMV). It is characterized by a rapid onset inflammation with necrotizing retinitis, vasculitis, and neuritis.

Initial symptoms of ARN include pain, light sensitivity, floaters and decrease in vision. Herpes simplex 1 and 2 are commonly the infectious agent. Varicella zoster also occurs, though is more common in immunocompromised patients. Patients often describe coexisting or recent herpetic infection. The affected population is usually young and healthy.

The diagnosis of ARN is made by the classic clinical appearance. Ancillary labs including hematologic testing for HSV 1 and 2 IgG/IgM and VZV IgG/IgM are ordered. PCR for viral elements of the CSF, vitreous, or aqueous may be performed.

The clinical course of ARN is for rapid spread and coalescence of the retinitis in about two weeks time. The infection and inflammation do not follow any vessels and end in the retinal periphery. Regression begins at about six weeks. The infected retina becomes severely atrophic. Holes within affected retina can lead to retinal detachment.

Treatment for ARN involves antiviral therapy. Acyclovir given intravenously for 7-10 days is the standard of care. If the response is determined to be inadequate, intravenous or intravitreal ganciclovir or foscarnet may be given. Oral Valtrex (valacyclovir) is sometimes used as a first-line therapy. This is usually done in more mild cases or in patients who would have difficulty receiving an IV infusion.

Response to treatment is usually noticeable by about four days. Topical or systemic steroids can be given when thought to be safe. The second eye is involved in about a third of cases. This can occur within a few weeks or many years later. The spread may be through the central nervous system or hematologically. Long term suppressive therapy is sometimes provided to patients with a tendency towards recurrence.

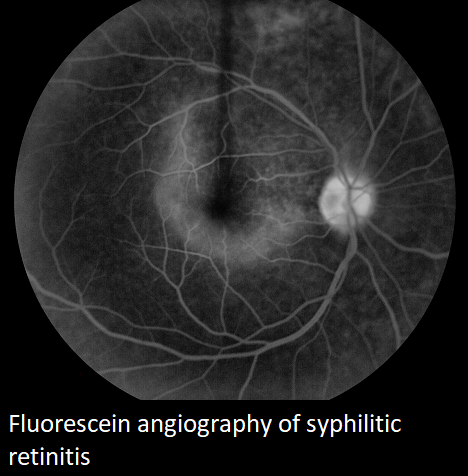

Retinal Syphilis

Retinal syphilis is a rare cause of HNR. It is due to the infective agent Treponema pallidum, a thin spiral shaped bacterium. Humans are the only known host, and transmission is usually sexual, though it can occur congenitally or from blood transfusion.

The incidence of syphilis has been falling in the past seventy years. There was a small spike with WWII, and in the 1980’s due to an increase in unprotected homosexual activity.

Ocular manifestations of syphilis include uveitis, keratitis, vitritis, retinitis, choroiditis, and optic neuritis. Serous retinal detachments are sometimes seen.

The diagnosis of retinal syphilis is based upon a high level of clinical suspicion. Blood tests, specifically FTA-ABS or MHA-TP, are 98% sensitive.

Treatment for ocular syphilis is equivalent to that of neurosyphilis, requiring intravenous penicillin for 10 to 14 days, followed by intramuscular penicillin weekly for 3 weeks. This duration of treatment is necessary because of the barrier of antibiotics reaching the intraocular fluid due to the blood ocular barrier. The majority of patients have resolution of their disease and do quite well.

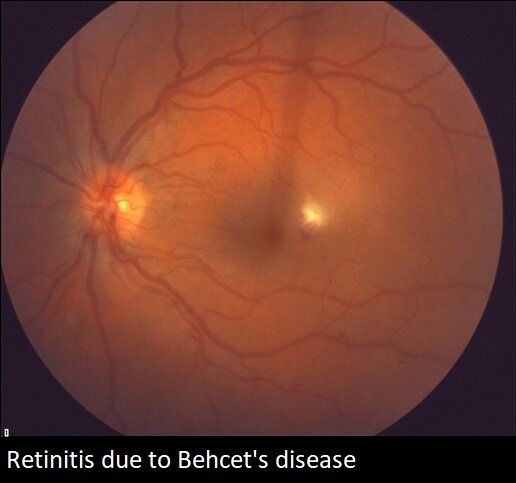

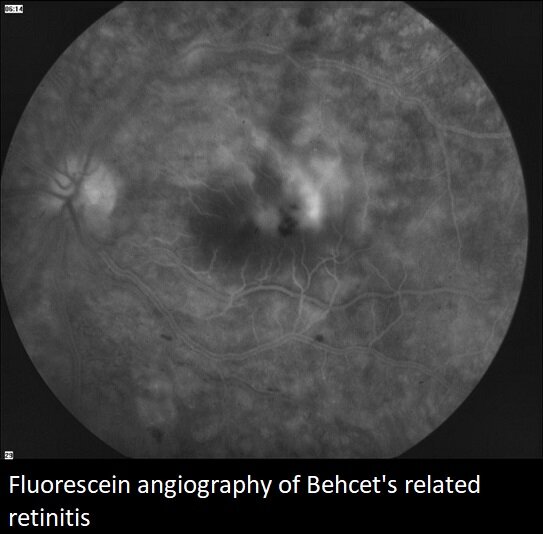

Behçet’s Disease

Behçet’s disease is an inflammatory disorder which most commonly affects the mouth, genitalia, and eyes. Arthritis of large joints also occurs. Vascular and brain inflammation are also possible, and if not treated, may be fatal.

The diagnosis of Behçet’s disease is made based upon clinical findings, as well as a positive skin pathergy test.

Behçet’s disease has a genetic component and is more prevalent in the Middle East, Far East, and in the Mediterranean. In America, approximately 1/250,000 people have Behçet’s disease.

Etiologically, Behçet’s disease is an immune complex deposition disorder with T cell and neutrophil cell activation, secondary vasculitis and tissue destruction.

Clinically, patients with Behçet’s disease often experience aggressive bilateral uveitis. The events are recurrent and may be explosive. Posterior segment involvement is common and includes vitritis, occlusive vasculitis, and retinal necrosis.

Treatment of Behçet’s disease requires aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy. Corticosteroids are the first-line therapy, through often inadequate. Biologic therapy is becoming more commonly used. Combination treatment is often necessary given the severe and aggressive nature of the disease.

The prognosis without treatment is very poor and the majority of patients will become legally blind. With early diagnosis and appropriate therapy most Behçet’s disease patients do quite well.

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis is another aggressive inflammation disorder which involves the eyes and may cause HNR. The classic triad in Wegener’s granulomatosis includes necrotizing granulomatosis of the upper and lower respiratory tract, glomerulitis of the kidneys, and necrotizing vasculitis.

When Wegener’s granulomatosis involves the eye, it often times will cause retinitis, vasculitis, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal detachment. Ocular involvement occurs in nearly half of patients and is often times severe. Scleritis and orbital inflammation may also occur.

Immunosuppressive treatment for Wegener’s granulomatosis is necessary for survival. Untreated patients live on average of five months, and the one year survival is less than 20%. With therapy, long term survival and disease remission is the rule. Corticosteroids with adjunctive therapy as in Behçet’s is usually necessary.

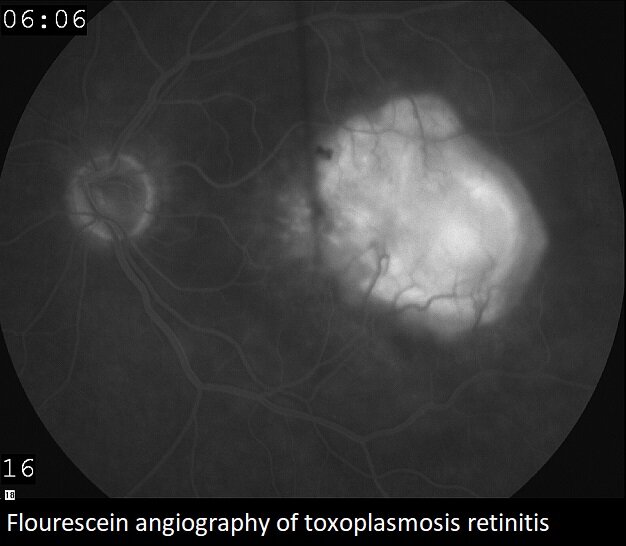

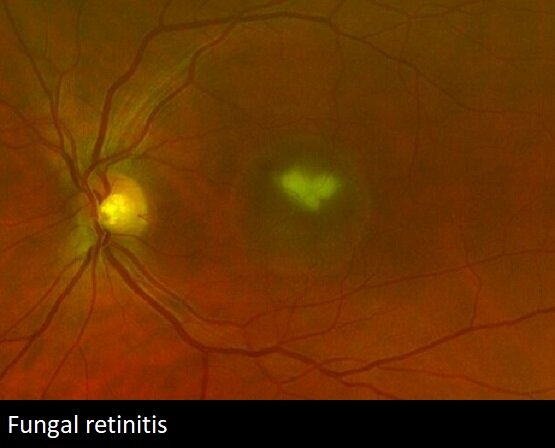

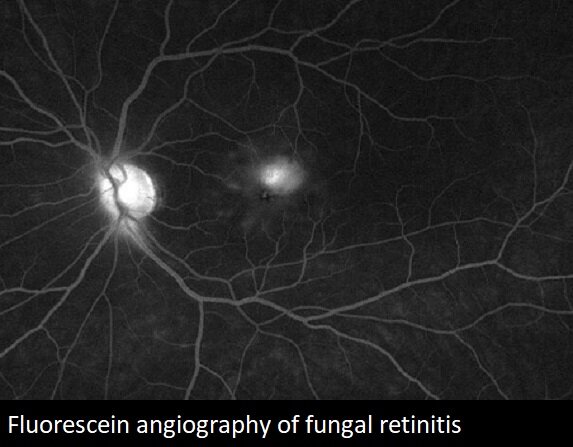

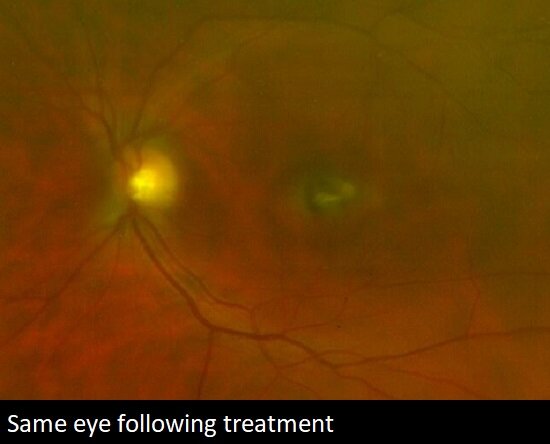

Toxoplasmosis and Fungal Retinitis

Toxoplasmosis and fungal infections are also causes of retinitis. Their findings are usually classic for parasitic or fungal infection, and usually not confused with the other more aggressive etiologies. Treatment for toxoplasmosis, an infection caused by the Toxoplasma gondii parasite, is elective, and performed when the infection threatens the optic nerve or central macula. Fungal infection usually occurs either due to trauma or hematologic spread, usually from intravenous drug abuse or indwelling catheters. Treatment involves systemic and intravitreal antifungal therapy.

From the Expert…

Hemorrhagic necrotizing retinitis is the most aggressive inflammatory condition of the eye that an ophthalmologist will encounter. Several conditions can cause this, though it is most likely due to herpes simplex or varicella zoster, syphilis, Behçet’s disease, or Wegener’s granulomatosis. The findings are variable, though there are many commonalities in the clinical presentation.

Without accurate diagnosis and early intervention, the prognosis is universally poor. The ophthalmologist must lead the work up and the management. Infectious disease physicians and rheumatology are important contributors to the patient’s care.

Additional Resources

Wender et al. How to Recognize Ocular Syphilis. Review of Ophthalmology. Published 20 November 2008. https://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/article/how-to-recognize-ocular-syphilis. Accessed 21 October 2019.

Ahuja et al. Infectious Retinitis: A Review. Retinal Physician. Published 1 November 2008. https://www.retinalphysician.com/issues/2008/nov-dec/infectious-retinitis-a-review. Accessed 21 October 2019.

Schoenberger et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Retinal Necrosis: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2017;124:382-392.

Verity et al. Behcet’s disease: from Hippocrates to the third millennium. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:1175-1183.

Zhang AY and Reddy AK. The 4-1-1 on Infectious Retinitis: Challenges in the diagnosis and management of fungal endophthalmitis. Retina Today 2018;May/June:36-41.

Kim et al. Interventions for Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2013;120:371-378.

Pakrou N, Selva D, Leibovitch I. Wegener’s Granulomatosis: Ophthalmic Manifestations and Management. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2006;35:284.292.